"How do you do. My name is Deems Taylor, and it's my very pleasant duty to welcome you here on behalf of Walt Disney, Leopold Stokowsky and all the other artists and musicians whose combined talents went into the creation of this new form of entertainment, Fantasia."

So began Walter Elias Disney's most audacious experiment in the field of animation. Four years previously he had mortgaged his house and practically his entire career on the reckless venture of a cartoon feature film, Snow White and the Seven Dwarfs, and the results paid handsome dividends. From this seminal moment, a new genre of film was born, and Disney was able to

push the boat out with further adventures in the feature length animation field, as well as the further adventures of his "star" originally to be known as Mortimer Mouse (named after the camera whose reels his ears mimicked), later changed to Mickey.

push the boat out with further adventures in the feature length animation field, as well as the further adventures of his "star" originally to be known as Mortimer Mouse (named after the camera whose reels his ears mimicked), later changed to Mickey.Thus it was that Disney approached Leopold Stokowsky with a view towards making a cartoon short version of Dukas's The Sorcerer's Apprentice. The end result however, was something considerably more ambitious.

It was a film that I had known about since the 1970s, from looking at posters in the London Underground stations; the cartoons of Walt Disney were as rich and prosperous a commodity as they are today, but this particular one seemed a little unusual, which even a child of my age would notice. The one unmistakable image was that of Mickey Mouse, but the rest of it seemed puzzling: what was the title about? Why wasn't it a Mickey type cartoon adventure? Where was the story? And what were all those other strange things around him?

Such an impression led to an aura of mystique around the film, so that when I did finally get round to seeing it in 1990 (on the film's 50th anniversary) at the new Odeon Ipswich, I was curious to the point of wonderment, and found it an incredibly beautiful film, having grown up enough to be able to appreciate it as not just a cartoon. The children of the 1990's however, were just as mystified as children of the 1970's (or indeed the 1940's) - "When's Mickey coming on, Dad?", I heard a child ask in the cinema in Ipswich that afternoon. I suspect many other children have asked their parents that question in cinemas through the decades.

Youngsters may not have expected the arty tones to the film, but this doesn't alter the brilliance of the animations, which all work on their own different levels. The first of them is a slightly uncharacteristic rendition of Bach's Tocata and Fugue, unusual not for the abstract animation, but for Stokowsky's

orchestration of a piece originally written for organ. This was no doubt to allow Stokowsky and his orchestra full reign to their talents.

orchestration of a piece originally written for organ. This was no doubt to allow Stokowsky and his orchestra full reign to their talents.A rousing, stylish start nonetheless, followed equally audaciously by Tchaikovsky's The Nutcracker Suite, perhaps the most charming of all the animations, with characteristic Disney flourishes of imagination such as Chinese mushroom dancers and Cossack dancing thistles.

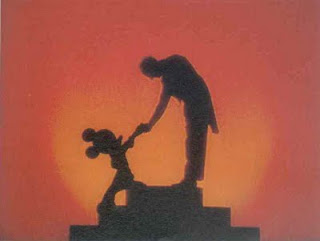

Next comes the long-awaited arrival of The Sorcerer's Apprentice; as the erstwhile Mr. Taylor puts it, "a piece that tells a very definite story", and formed the basis for the whole project. It's the one item of all that seems most in tune with what would be perceived to be the "Disney style" (if one thinks of the "Silly Symphonies" they had been producing for years), and in that sense is probably the most successful of the lot. It certainly sold this otherwise unsellable film by putting Mickey on the front of the posters.

After the mischievous exploits of Mickey the Sorcerer's Apprentice, comes something altogether different in The Rite of Spring, which was always a very experimental and ritualistic piece as composed by Igor Stravinsky, and a highly unusual piece for Walt Disney to challenge. As an adaptation of the music, it chops and changes with uncomfortable melodies to listen to, and as animation it's variable but certainly has its moments, and Disney has rarely dared to push the barriers further than this.

As if to trivialise things after the primal experience of the story of the beginning of the Earth in

The Rite of Spring, there comes an intermission (in the tradition of a "Concert Feature") where a soundtrack line makes various noises and wave forms, before the second half of the concert/film commences with The Pastoral Symphony, only partly trivialised by switching to a mythical setting. Its difficult not to recognise a certain My Little Pony imagery with parts of this sequence; secretly I also wonder if it was considered politically incorrect to depict Beethoven's beloved Austria because of its connections to the Nazis in World War II (The Ride of the Valkyries was also a piece considered and ultimately rejected by Disney), but Beethoven's music still transcends the prissiness of the visuals, and there are still some charming moments such as the storm and the party of revellers.

The Rite of Spring, there comes an intermission (in the tradition of a "Concert Feature") where a soundtrack line makes various noises and wave forms, before the second half of the concert/film commences with The Pastoral Symphony, only partly trivialised by switching to a mythical setting. Its difficult not to recognise a certain My Little Pony imagery with parts of this sequence; secretly I also wonder if it was considered politically incorrect to depict Beethoven's beloved Austria because of its connections to the Nazis in World War II (The Ride of the Valkyries was also a piece considered and ultimately rejected by Disney), but Beethoven's music still transcends the prissiness of the visuals, and there are still some charming moments such as the storm and the party of revellers.The funniest and perhaps most enjoyable of the pieces for me is The Danc

e of the Hours, an unashamed parody of Ponchielli's ballet but quite appropriate considering the jollity of the piece, with balletic ostriches, hippos (the inspiration for those "Hippapotamousse" ads in the 80's?), elephants (two years before Dumbo came along) and amorous crocodiles, all coming together in a delightful finale.

e of the Hours, an unashamed parody of Ponchielli's ballet but quite appropriate considering the jollity of the piece, with balletic ostriches, hippos (the inspiration for those "Hippapotamousse" ads in the 80's?), elephants (two years before Dumbo came along) and amorous crocodiles, all coming together in a delightful finale.The "big finish comes" with Mussourgsky's Night on Bald Mountain and Schubert's Ave Maria, a beautifully powerful mixture of "the profane and the sacred", with the sight of Satan atop the mountain (looking very Darth Vader-ish) demonstrating the darker element that often permeated Disney's work. The beautiful ending representing the triumph of good over evil (darkness gives way to light) w

as done with innovative multi-plane animation, ending with a sunset to conclude Fantasia, which at the time (and still today) in the eyes of some was considered pretentious, and was not a huge success. If it was a failure, then it was one of Disney's most glorious ones, a brilliant attempt at integrating mass entertainment and art, and an experience of pure cinema.

as done with innovative multi-plane animation, ending with a sunset to conclude Fantasia, which at the time (and still today) in the eyes of some was considered pretentious, and was not a huge success. If it was a failure, then it was one of Disney's most glorious ones, a brilliant attempt at integrating mass entertainment and art, and an experience of pure cinema.In the sixty years since Fantasia there were many attempts at reviving the formula of classical music set to animation: the original film went through various re-releases, with the 1982 version having the audacity to completely re-record the music (as previously orchestrated by Stokowsky) to the original animation.

There was much talk of a sequel, with various composers considered for animated treatment (including even The Beatles at one stage), but in 1999 the Disney studio bravely and perhaps foolishly set about trying to follow-up its original masterpiece with FANTASIA 2000, commemorating the new millennium in enjoyable fashion with Donald and Daisy Duck in a cheerfully apocalyptic rendition of the Noah's Arc story to the tune of Elgar's Pomp and Circumstance. Other pieces followed a pretty similar pattern to the original, with an abstract opening (to the beginning of Beet

hoven's 5th Symphony) followed by a charming rendition of flying whales to Respighi's Pines of Rome, and finishing once again with the good vs. evil motif of Stravinsky's Firebird suite. Perhaps the most innovative piece was Copeland's Rhapsody in Blue animated to the newspaper drawings of Al Hirschfield.

hoven's 5th Symphony) followed by a charming rendition of flying whales to Respighi's Pines of Rome, and finishing once again with the good vs. evil motif of Stravinsky's Firebird suite. Perhaps the most innovative piece was Copeland's Rhapsody in Blue animated to the newspaper drawings of Al Hirschfield.In spite of the shortening of the music down to single movements rather than entire symphonies, as well as irritating celebrity introductions (from the likes of Steve Martin, Bette Midler, James Earl Jones and the conductor himself, James Levine), there was still a great deal of charm to the enterprise, although less of the magic that Walt brought to the original.

And it was testament to the memory of the original, that Mickey's Sorcerer's Apprentice was revived for the sequel 60 years later.